I’m the tenth editor ofNational Geographicsince its founding in 1888. I’m the first woman and the first Jewish person—a member of two groups that also once faced discrimination here. It hurts to share the appalling stories from the magazine’s past. But when we decided to devote ourApril magazineto the topic of race, we thought we should examine our own history before turning our reportorial gaze to others.

Race is not a biological construct, as writerElizabeth Kolbert explains in this issue, but a social one that can have devastating effects. "So many of the horrors of the past few centuries can be traced to the idea that one race is inferior to another,” she writes. "Racial distinctions continue to shape our politics, our neighborhoods, and our sense of self.”

How we present race matters. I hear from readers thatNational Geographicprovided their first look at the world. Our explorers, scientists, photographers, and writers have taken people to places they’d never even imagined; it’s a tradition that still drives our coverage and of which we’re rightly proud. And it means we have a duty, in every story, to present accurate and authentic depictions—a duty heightened when we cover fraught issues such as race.

PHOTOGRAPH BY FRANK AND HELEN SCHREIDER, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CREATIVE

We askedJohn Edwin Masonto help with this examination. Mason is well positioned for the task: He’s a University of Virginia professor specializing in the history of photography and the history of Africa, a frequent crossroads of our storytelling. He dived into our archives.

What Mason found in short was that until the 1970sNational Geographicall but ignored people of color who lived in the United States, rarely acknowledging them beyond laborers or domestic workers. Meanwhile it pictured "natives” elsewhere as exotics, famously and frequently unclothed, happy hunters, noble savages—every type of cliché.

Unlike magazines such asLife,Mason said,National Geographicdid little to push its readers beyond the stereotypes ingrained in white American culture.

"Americans got ideas about the world from Tarzan movies and crude racist caricatures,” he said. "Segregation was the way it was.National Geographicwasn’t teaching as much as reinforcing messages they already received and doing so in a magazine that had tremendous authority.National Geographiccomes into existence at the height of colonialism, and the world was divided into the colonizers and the colonized. That was a color line, andNational Geographicwas reflecting that view of the world.”

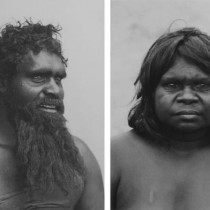

Some of what you find in our archives leaves you speechless, likea 1916 story about Australia. Underneath photos of two Aboriginal people, the caption reads: "South Australian Blackfellows: These savages rank lowest in intelligence of all human beings.”

Questions arise not just from what’s in the magazine, but what isn’t. Mason compared two stories we did about South Africa,one in 1962, theother in 1977. The 1962 story was printed two and a half years after the massacre of 69 black South Africans by police in Sharpeville, many shot in the back as they fled. The brutality of the killings shocked the world.

PHOTOGRAPH BY JAMES P. BLAIR, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CREATIVE

"National Geographic’s story barely mentions any problems,” Mason said. "There are no voices of black South Africans. That absence is as important as what is in there. The only black people are doing exotic dances … servants or workers. It’s bizarre, actually, to consider what the editors, writers, and photographers had to consciously not see.”

Contrast that with the piece in 1977, in the wake of the U.S. civil rights era: "It’s not a perfect article, but it acknowledges the oppression,” Mason said. "Black people are pictured. Opposition leaders are pictured. It’s a very different article.”

Fast-forward to a2015 story about Haiti, when we gave cameras to young Haitians and asked them to document the reality of their world. "The images by Haitians are really, really important,” Mason said, and would have been "unthinkable” in our past. So would our coverage now of ethnic and religious conflicts,evolving gender norms, the realities of today’s Africa, and much more.

PHOTOGRAPH BY SMITH NEUVIEME, FOTOKONBIT

Mason also uncovered a string of oddities—photos of "the native person fascinated by Western technology. It really creates this us-and-them dichotomy between the civilized and the uncivilized.” And then there’s the excess of pictures ofbeautiful Pacific-island women.

"If I were talking to my students about the period until after the 1960s, I would say, ‘Be cautious about what you think you are learning here,’ ” he said. "At the same time, you acknowledge the strengthsNational Geographichad even in this period, to take people out into the world to see things we’ve never seen before. It’s possible to say that a magazine can open people’s eyes at the same time it closes them.”

April 4 marks the 50th anniversary of the assassination ofMartin Luther King, Jr.It’s a worthy moment to step back, to take stock of where we are on race. It’s also a conversation that is changing in real time: In two years, for the first time in U.S. history, less than half the children in the nation will be white. So let’s talk about what’s working when it comes to race, and what isn’t. Let’s examine why we continue to segregate along racial lines and how we can build inclusive communities. Let’s confront today’s shameful use of racism as a political strategy and prove we are better than this.

For us this issue also provided an important opportunity to look at our own efforts to illuminate the human journey, a core part of our mission for 130 years. I want a future editor ofNational Geographicto look back at our coverage with pride—not only about the stories we decided to tell and how we told them but about the diverse group of writers, editors, and photographers behind the work.

We hope you will join us in this exploration of race, beginning this month and continuing throughout the year. Sometimes these stories, like parts of our own history, are not easy to read. But asMichele Norris writes in this issue, "It’s hard for an individual—or a country—to evolve past discomfort if the source of the anxiety is only discussed in hushed tones.”

0

0

For Decades, Our Coverage Was Racist. To Rise Above Our Past, We Must Acknowledge It

We asked a preeminent historian to investigate our coverage of people of color in the U.S. and abroad. Here's what he found.VIEW IMAGES In a full-issuearticle on Australiathat ran in 1916, Aboriginal Australians were called "savages"